Expectations Smashed by LOC's Macbeth

Have you ever attended a particular performance, expecting anything from mediocrity to pure filth, only to be completely and pleasantly surprised by a great evening of opera? Such an experience confronted me Wednesday night, November 24, when I saw Lyric Opera of Chicago and Houston Grand Opera's co-production of Verdi's Macbeth.

Several correspondents from Houston condemned this production as the ultimate in Eurotrash, what with its inclusion of such elements as witches in black overcoats and film footage for the spectral presentation of Banquo's kingly lineage. Further, I was dreading Catherine Malfitano's Lady Macbeth. Her last few outings at Lyric--Jenny in Weill's Mahagonny and Beatrice in Bolcom's View from the Bridge--were less-than-successful, showing a woman in the throes of a major vocal crisis. As the production design and the woman playing Lady Macbeth are rather important elements in this opera, I headed downtown with the lowest hopes for every aspect of this particular evening at the opera other than what I expected to be a fine Macbeth from German superstar baritone Franz Grundheber.

So, imagine my surprise when I--he who so loves traditional, faithful representations--found myself loving this production. Director David Alden gives us a Macbeth in which all aspects of plot and scene are the imagined products of an insane Macbeth. The witches, a nondescript army of black coats, and the banquet guests, a bland assortment of nobodies, have no personalities aside from the way in which Macbeth imagines them. The other main characters are well-developed independently of Macbeth, but they become complete only when viewed in relationship to Macbeth himself. Thus, Lady Macbeth's goal is to motivate Macbeth to help her attain power, Macduff's primary ambition is to murder Macbeth, Banquo aims to survive a walk in the dark without being killed by Macbeth's henchmen. Macbeth, one of literature's most ambivalent characters, is presented as a man about whom no one can have a neutral feeling.

Set designer Charles Edwards' off-the-wall physical accoutrements match Alden's conception of the screwy inner world of Macbeth. Images of a mental ward and a married couple's living room rapidly interchange, as if asking the viewer how different those environments actually are. When storming the castle, Macduff and Malcolm literally tear down the walls of Macbeth's house, perhaps alluding to the utter destruction a group can bring when they interfere in the private lives of their leaders. The trench created for the witches worked in presenting their breaking of the fourth wall and the wide variety of furniture Edwards gave Malfitano to mount and straddle added to her sexually charged characterization.

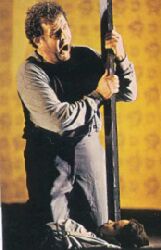

As the story of Macbeth is one of Shakespeare's most blatant dismantlings of the unities of time and place, this production, while still cogent in the grander sense, focuses on individual moments to achieve its impact. One such moment is when Macbeth prepares for his battle against Macduff and his Birnam Wood-clad followers. Rather than donning armor as the libretto suggests, Macbeth wraps himself in a banner which reads "Nessun nato di donna" (No one borne of a woman), illustrating the protective powers of delusional ideas. Moments like these remained on the proper side of the fine line between oblique suggestion and hammering the audience over the head.

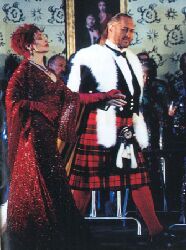

Given such a fine physical and pyschological world to inhabit clearly benefited the performers. Malfitano, in particular, posited herself wonderfully into the elements surrounding her, combining a shockingly good vocal performance with a unique portrayal of the role. From the moment she first took the stage, offering a haunting reading of Macbeth's letter in a decrepit sotto voce, it became apparent that Malfitano's Lady Macbeth would be like no one else's. The recorded history of this role is a great one, with such interpreters as Callas, M÷dl, Ludwig, and Rysanek notorious for the role. Malfitano, clearly cognizant of those performances, seems to have her own ideas about Lady Macbeth. Portraying the same immense desire for power as her predecessors, Malfitano adds a sexual lust into the mix, yielding a riveting Lady Macbeth ready to pounce at a moment's notice. Such impetuosity was matched by her sometimes-ragged, always-fascinating vocal portrayal. In a strong "Vieni, t'affretta" Malfitano's sometimes-huge register breaks seemed ironed-over, delighting this listener with a more prominent chest voice than I'd ever heard from her. It is true that this chest voice is not natural to Malfitano's essentially lyric-coloratura instrument, but the method in which she has carved out a lower register is most successful. Rather than pounding down on the lowest notes, Malfitano supported them truthfully, finding power more in subtlety than brute force. The passage work in "Or tutti sorgete" was cleaner than, say, Cossotto or Ludwig, with almost as much fervor as those great ladies.

Malfitano really comprehends the descending character arc of Lady Macbeth and she provided a vocal portrayal to match the histrionic one. Her "La luce langue" showed some of the vocal and emotional seams coming undone, demonstrating a sickeningly blasÚ attitude toward crime with each panted "Nuovo delitto" and a frightening enjoyment of her new powers with a blaring "O scettro, alfin sei mio!" The Brindisi presented Malfitano in roaring-good voice. Frankly, I expected complete vocal breakdown by this point in the opera, but Malfitano rallied, returning to her coloratura roots to sing this scene with more ease than almost every other Lady Macbeth in recorded history. High notes were intact and grupetti were well-articulated and meaningful. Such a well-sung performance points toward Lady Macbeth's brilliance at keeping up the appearance of calm in the face of Macbeth's mad hallucinations.

Malfitano really comprehends the descending character arc of Lady Macbeth and she provided a vocal portrayal to match the histrionic one. Her "La luce langue" showed some of the vocal and emotional seams coming undone, demonstrating a sickeningly blasÚ attitude toward crime with each panted "Nuovo delitto" and a frightening enjoyment of her new powers with a blaring "O scettro, alfin sei mio!" The Brindisi presented Malfitano in roaring-good voice. Frankly, I expected complete vocal breakdown by this point in the opera, but Malfitano rallied, returning to her coloratura roots to sing this scene with more ease than almost every other Lady Macbeth in recorded history. High notes were intact and grupetti were well-articulated and meaningful. Such a well-sung performance points toward Lady Macbeth's brilliance at keeping up the appearance of calm in the face of Macbeth's mad hallucinations.

The only moment of the evening in which Malfitano's power proved lacking was the vengeance duet, "Ora di morte e di vendetta," which closes Act Three. Malfitano simply could not match Grundheber for vocal power, although the look of pure hatred on her face was memorable.

The night I attended, Malfitano sang the Sleepwalking Scene's final pianissimo D rather successfully. In subsequent performances, I am told, the note deserted her most pathetically. No matter. While the D can be a lovely effect, that note is not what this scene is about. Malfitano's presentation of the final moments of the obsessive, distracted Lady Macbeth was simply brilliant. With aching specificity (I won't forget how she murmured "Di Fiffe il Sire sposo e padre or or non era?...") and frayed tone, Malfitano more than met the requirements of this great scene.

Unlike Lyric's prima donna-centered production of La BohŔme in which all but Freni failed to impress, (Matthew Epstein and) Chicago's darling Malfitano was given quite the supporting cast. In particular, Franz Grundheber's Macbeth ranks as the most Italianate performance I've ever heard from a non-Italian, much less a German. Known for his brilliant Wozzeck and Dutchman, Grundheber can now count a dazzling Macbeth in his gallery of great portrayals. The range from the despair of his final cabaletta, "PietÓ, rispetto, amore," to the wonder of "Fuggi, regal fantasma" in the Apparition Scene was striking. Brilliant top notes were quite present and that luscious middle voice was also used to tremendous effect, particularly in his first act contemplation of murder, "Mi si affaccia un pugnal?" Grundheber was staggering both in sound and portrayal in the Banquet Scene, providing a psychotic portrayal reminiscent of his Wozzeck. A masterful sense of dramatic pacing and the ability to control the stage for a long period of time was demonstrated in a superb Act Three. Macbeth's final pathetic moments, including the contemplation of the corpse of Lady Macbeth and his cursing of the witches for offering such perplexing prophecies, were quite touching. I look forward to so much more from this great artist; I can already hear great Renatos, Amonasros, and Ernani and Forza Carlos from Grundheber.

Unlike Lyric's prima donna-centered production of La BohŔme in which all but Freni failed to impress, (Matthew Epstein and) Chicago's darling Malfitano was given quite the supporting cast. In particular, Franz Grundheber's Macbeth ranks as the most Italianate performance I've ever heard from a non-Italian, much less a German. Known for his brilliant Wozzeck and Dutchman, Grundheber can now count a dazzling Macbeth in his gallery of great portrayals. The range from the despair of his final cabaletta, "PietÓ, rispetto, amore," to the wonder of "Fuggi, regal fantasma" in the Apparition Scene was striking. Brilliant top notes were quite present and that luscious middle voice was also used to tremendous effect, particularly in his first act contemplation of murder, "Mi si affaccia un pugnal?" Grundheber was staggering both in sound and portrayal in the Banquet Scene, providing a psychotic portrayal reminiscent of his Wozzeck. A masterful sense of dramatic pacing and the ability to control the stage for a long period of time was demonstrated in a superb Act Three. Macbeth's final pathetic moments, including the contemplation of the corpse of Lady Macbeth and his cursing of the witches for offering such perplexing prophecies, were quite touching. I look forward to so much more from this great artist; I can already hear great Renatos, Amonasros, and Ernani and Forza Carlos from Grundheber.

Roberto Aronica's ringing, plangent tenor breezed through "Ah, la paterna mano" and the following duet with Malcolm, also well-sung by the devilishly handsome Michael Sommese. Aronica has big plans for the future, including Alfredo at the Met, Duca di Mantua for Houston, and Des Grieux for Bilbao; I have no doubt that he will find great success in these assignments. I hope he returns to Lyric soon.

Only Raymond Aceto's overly gruff Banquo disappointed. "Come dal ciel precipita" can be a beautiful moment of respite in this otherwise-stormy opera (listen to recordings by Ramey and Tajo for examples of such a phenomenon), but Aceto, an alumnus of the Met Young Artist Program, was not up to the aria's demands. Nothing about his top E's was exciting and the aria was missing the fluid legato Verdi so lovingly assigned to one of his best basso cantate moments.

Conductor Asher Fisch kept the orchestra together well enough, but without any individual stamp. At the hands of an Abbado or a de Sabata, Macbeth can be a great opera, proving early middle period Verdi every bit as exciting as the beloved middle period operas and the fantastic late period works. However, at the hands of Fisch, the singers were forced to shoulder the legislation of Macbeth's musical greatness. In spite of Fisch, Malfitano, Grundheber, and Aronica clearly demonstrated what a great night of music theatre Macbeth can be.

Attention Wagnerites--even you may like it!

--Doug, who believes Verdi still can be performed

|

Literary content: Copyright: © 1999 Doug Peck |

| TOP of PAGE |

Welcome Page | Site Map

| Website Design by: |

|

|