and a performance of it for the ages.

Giacomo Puccini's La Fanciulla del West is a glaringly uneven opera.  It took two librettists, with a few contributions by Puccini himself, to turn David Belasco's play about the American Wild West into a libretto. It was one thing for Puccini to immerse himself into Japanese culture for BUTTERFLY but quite another for him to assimilate a cowboy and American Indian culture of bar rooms and lynchings that he was light years removed from. It's not a great libretto and it's embarrassingly silly at times as it tries to depict the Wild West during the Gold Rush days, with grizzled gun-toting miners and a character named Wowkle howling "Ugh….Ugh." The libretto produces unintended chuckles in spots, and one winces at lines such as "Hello Mr. Ashby dell'Agenzia Welles Fargo" ("Hello Mr. Ashby of the Wells Fargo Agency") or bar room references to "Whiskey ed acqua" ("Whiskey and water"). There are many more.

It took two librettists, with a few contributions by Puccini himself, to turn David Belasco's play about the American Wild West into a libretto. It was one thing for Puccini to immerse himself into Japanese culture for BUTTERFLY but quite another for him to assimilate a cowboy and American Indian culture of bar rooms and lynchings that he was light years removed from. It's not a great libretto and it's embarrassingly silly at times as it tries to depict the Wild West during the Gold Rush days, with grizzled gun-toting miners and a character named Wowkle howling "Ugh….Ugh." The libretto produces unintended chuckles in spots, and one winces at lines such as "Hello Mr. Ashby dell'Agenzia Welles Fargo" ("Hello Mr. Ashby of the Wells Fargo Agency") or bar room references to "Whiskey ed acqua" ("Whiskey and water"). There are many more.

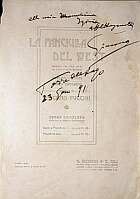

Yet Puccini firmly believed he could compose an opera on this subject that would be "more daring, more vigorous and on a larger scale than La Bohème," words he wrote to his publisher Giulio Riccordi. While it is true that Fanciulla is more vigorous and on a larger scale than the more intimate Bohème, and Puccini's craftsmanship and musical language are certainly more advanced, it has none of the elegance, youthful charm and effervescent energy that Bohème possesses. Weighed down by a libretto not taken seriously by modern audiences, the difficulty of the three lead roles, heavy orchestration, and cartoon-like characters, Fanciulla has too much working against it. Some of Puccini's music isn't very good either, particularly the music he wrote to depict a snowstorm, perhaps more appropriate in a grade "B" Western movie, or that thundering music that concludes the second act. Moreover, just about all the characters in Fanciulla are remote and unsympathetic in comparison to those in Bohème, and it is only Minnie who elicits much sympathy.

Toscanini conducted the first performances at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1910, with a stellar cast that included Emmy Destinn and Enrico Caruso. Although it was composed especially for the Met, its initial success quickly cooled with New York audiences and it was soon out of the repertory. It remains an ugly duckling in Puccini's canon, usually only staged when an opera company can find a Minnie who can get through the role and not drip blood all over the stage.

Incredible as it may seem, Puccini considered Fanciulla to be his best opera but over the years it has remained his least popular, probably due to the work's pronounced lack of Puccini's trademark, hummable arias. I think this is the main reason audiences have not embraced it. The orchestra is the main protagonist, abetted by the chorus, as is the case in Turandot but Turandot has a slew of gorgeous arias. The score does show considerable development from the adventurous harmonies he employed in Madama Butterfly. His use of the "whole tone scale" and augmented intervals and dissonances takes him farther afield from anything he composed before. But the arias are second-rate and only the short tenor aria in the third act "Ch'ella me creda libero e lontano" ("Let her believe that I escaped and am free") comes close to being popular. Few indeed are the sopranos who have done Minnie's only aria "Laggiù nel Soledad" in a concert or recital, much less recorded it on a disk of Puccini arias.

The music is difficult to sing and the singers aren't helped by an orchestration that is formidable. The role of Minnie is deemed a killer role for the soprano, very hard on the voice and best avoided by all but the most dramatic voices. Few of the really dramatic voices will touch it though. The tenor role has fared better and while it is also very demanding vocally, it has had a few very successful exponents in Placido Domingo, and earlier in Corelli and Richard Tucker. If anything, Fanciulla tends to appeal to a few conductors who enjoy the lush orchestral score and large amount of choral writing. It is ironic, and unfair, though that Fanciulla - a score Ravel considered so good that he assigned it to his students to study -- has been ignored by just about all of the so-called "great" conductors.

Recordings of Fanciulla have been uneven as well. Only the Tebaldi-Del Monaco stereo recording for Decca has come close to doing it justice but Tebaldi strains mightily to get out the notes. Her sound was rather matronly by the time she recorded the role in 1958 and her flattish, wide-open approach to top notes is not always a thing of beauty. She gets out the notes but what a blast they are. Del Monaco was never captured very well on disk and he comes off as he usually did, a coarse bellower, slightly under pitch at times, and unable to sustain much soft singing, although Decca's hard, brittle acoustic doesn't help him. The conducting is uninspired. Birgit Nilsson recorded Minnie in 1961 for EMI (when Maria Callas supposedly turned it down -- like she could have sung Minnie in 1961!). But the recording was pretty awful, thanks in part to her often-shrill singing partnered with an inadequate tenor and mediocre conducting. Carol Neblett recorded it with Domingo, and she too struggles with the role, and a video of a live performance from La Scala exists with Mara Zampieri as Minnie but it is quite excruciating to listen to. There have been a couple of other recordings but they all leave something to be desired.

Fanciulla has fared a little better in the opera house but "great" performances remain few and far between and what popularity it has had seems confined to opera houses in Italy. And unless Tebaldi was available, the Italian houses employed vampire-like sopranos such as Magda Oliviero or more recently Mara Zampieri, excruciating creatures to listen to. U.S. companies have tended to avoid it, though Chicago's Lyric Opera (often referred to as "La Scala West" in the Carol Fox days) mounted a production in 1956 with Steber, Del Monaco and Mitropoulos repeating their success in Florence, and again in 1978 with Carol Neblett and Carlo Cossutta (and Marilyn Zschau doing two performances). Very recent performances in Los Angeles had a very miscast Catherine Malfitano as Minnie, supposedly losing her voice midway through the run, and Placido Domingo, who got through it somehow, but whose diminished vocal state caused him to transpose much of his role down.

Performances at the Metropolitan Opera in New York have also been uneven and the opera has had an intermittent history. Rudolf Bing, who took over the Met in 1950, didn't get around to offering it until the 1961-1962 season and he wouldn't spend the money on a new production, borrowing Lyric Opera of Chicago's. Nor were those performances trouble-free. Leontyne Price, the scheduled Minnie, only managed to sing five of the twelve performances, losing her voice in the second one and was replaced by Kirsten, and after it was over, Price had to stop singing for several months. One wonders what expert on voices convinced her that she could sing Minnie? Richard Tucker was fantastic as Johnson though and is on the broadcast, with Kirsten. He just sailed thorough this role with superb vocalism. It was revived during the last season in the old Met, again with Kirsten, and Corelli was a virile Johnson, and that performance was broadcast also.

For trivia buffs, Fanciulla had the dubious distinction of being the first full performance in the Met's new house at Lincoln Center. A student matinee with Beverly Bower and Gaetano Bardini took place in the new house on April 11, 1966, to fully test of the theater's acoustics for the first time. That performance was the 68th since the premiere in 1910. That evening, back in the old house, the performance was Tosca. It was the 468th performance of that work since it premiered at the Met in 1900, indicating Fanciulla's lack of popularity at the Met.

But earlier, there were four performances of Fanciulla in June 1954 at the Maggio Musicale in Florence. June 15, 1954, was a very good night to have been in the Teatro Communale. Dimitri Mitropoulos was the conductor, known for doing surprisingly marvelous performances of offbeat works such as Wozzeck and Elektra.

Mario Del Monaco was Johnson, Gian Giacomo Guelfi was Rance and Eleanor Steber was Minnie, the only American singer amid this bunch of Italians. The excellent Piero de Palma was Nick and in a bit of top drawer casting, Giorgio Tozzi was Jake Wallace. Although his character is gone after only ten minutes, the folk tune that Puccini borrowed for him to sing, "My Old Dog Tray" is the basis for one of the better scenes in the opera.

This performance is probably one of the best ever of this opera. Mitropoulos steals the show. He understands this work and conducts it like no other that I have heard. Puccini was constantly tinkering with his scores, often making changes for revivals, and in Fanciulla's case, there are supposedly eight versions, or variants, of the original score (Toscanini altered some of the instrumentation with Puccini's blessing before the first performance at the Met in 1910, already creating one of these different 'versions'). Mitropoulos does not use the "standard" version that we are accustomed to, but uses one that has additional music in Act I, and he uses the version of the Love Duet in Act II that Puccini added to the score for the Rome revival in 1922, which adds a few bars of music to the duet culminating with a high C for Minnie and Johnson which has to be held for several bars. It's murder to sing and it's no wonder this particular version of the duet is rarely done (and in fact the two singers at that Rome revival refused to sing the revised duet. I suppose shooting the two of them was out of the question?). The version of the score that Mitropoulos uses makes for interesting listening though, and the orchestral detail that he brings out, the breath and sense of line that he infuses into the score, his control of dynamics and rubato, are truly fantastic. His tempi are on the expansive side, emphasizing the score's inherent romanticism, but they don't drag either. It is truly superb work and I have marveled at what he does with this difficult score from day one.

Del Monaco and Guelfi sing extraordinarily well and Del Monaco in particular doesn't bellow as much as he sometimes did and even does some lovely soft singing. But the surprise performance is Eleanor Steber's. I couldn't believe it was really Eleanor the first time I heard it. Hers is not a voice one automatically thinks of when one thinks of Minnie. Her lirico voice was ideally suited to Eva, Sophie, Costanze, and the Countess. But Minnie? It's true that by 1954 she had grown tired of the cute lyric roles and had broadened her repertoire to include heavier roles such as Donna Anna, the Marschallin, the Empress and Elsa but they taxed her otherwise lyric instrument and Elsa, in particular, gave her fits. But on this occasion, she sailed through Minnie as if she were born to sing it. I can recall few performances from her of these more dramatic roles that surpass this in terms of sheer vocalism. It took my breath away.

Just about every note seems to have been thought about and is perfectly placed. She uses her voice carefully at times and there is a lot of soft, characteristically beautiful singing but the big notes are round and full-voiced and they are gorgeous. She loved working with Mitropoulos, and he with her, and it shows. Apparently Eleanor only agreed to do Minnie if Mitropoulos would be the conductor. Her confidence and scrupulous preparation were at an all time high as a result. She also endeared herself to the Florentines, working very hard with a horse, named Carola, which she rode daily through the city's parks and, naturally, onto the stage in the third act (much to Del Monaco's horror because he was deathly afraid of horses). She only sang the role four times during this run and while those performances were a microcosm of great singing, the white heat they generated was never duplicated. Minnie was not a role Eleanor's voice could have easily handled for any length of time. But what performances those were!

She sang one performance of Minnie at the Met in January of 1966, having been gone from the company for three years, called in at the last minute to replace Dorothy Kirsten who was ill and Beverly Bower, the understudy, who was in the hospital. Rumors persist that she was inebriated; Corelli (who had objected to singing the role of Johnson with Steber) was supposedly ill and walked out after the first act, necessitating the Met to drag Gaetano Bardini out of the audience, stuff him into some sort of a costume and have him finish the opera. It was a horrendous disaster. While her many adoring fans roared their approval, it was not one of Eleanor's best efforts, as a pirated tape of the performance indicates. By 1966, the dramatic roles had taken their toll on her voice and it was pretty much in shreds. Bing never called again. Except for Eleanor's participation in the Gala Farewell to the Old House on April 16, 1966, it was her last performance at the Metropolitan Opera. In retrospect though, she was probably no worse vocally than Malfitano was in Los Angeles recently.

Dorothy Kirsten's seemingly indestructible lyric instrument wouldn't appear to be tailor-made for Minnie either, but her cool, silvery sound could handle lirico spinto roles with a great deal of security if not a lot of volume but she handled Minnie's vocal terrors with an élan that was her trademark. She sang the role quite often, and quite well, managing Minnie's big notes very effectively. While I really prefer Kirsten's Minnie overall, with her endearingly vulnerable characterization, (I enjoy the way she quietly hums along with the orchestra prior to the duet in Act I in the Met broadcasts) Steber in 1954 did herself proud and is certainly on an equal footing with her in the Florence performance. Had I not heard this, I would never have believed Eleanor could have been this good. For those looking for a Fanciulla, this is the one to track down, along with both Met broadcasts with Kirsten and Tucker from 1962 and Kirsten and Corelli from 1966. They are all so-called 'pirates' so keep your eye patch and parrot handy. P13

|

Literary content: Copyright: © 2002 Parsifal13 |

| TOP of PAGE |

Welcome Page | Site Map

| Website Design by |

|

|